Data binding

Table of Contents

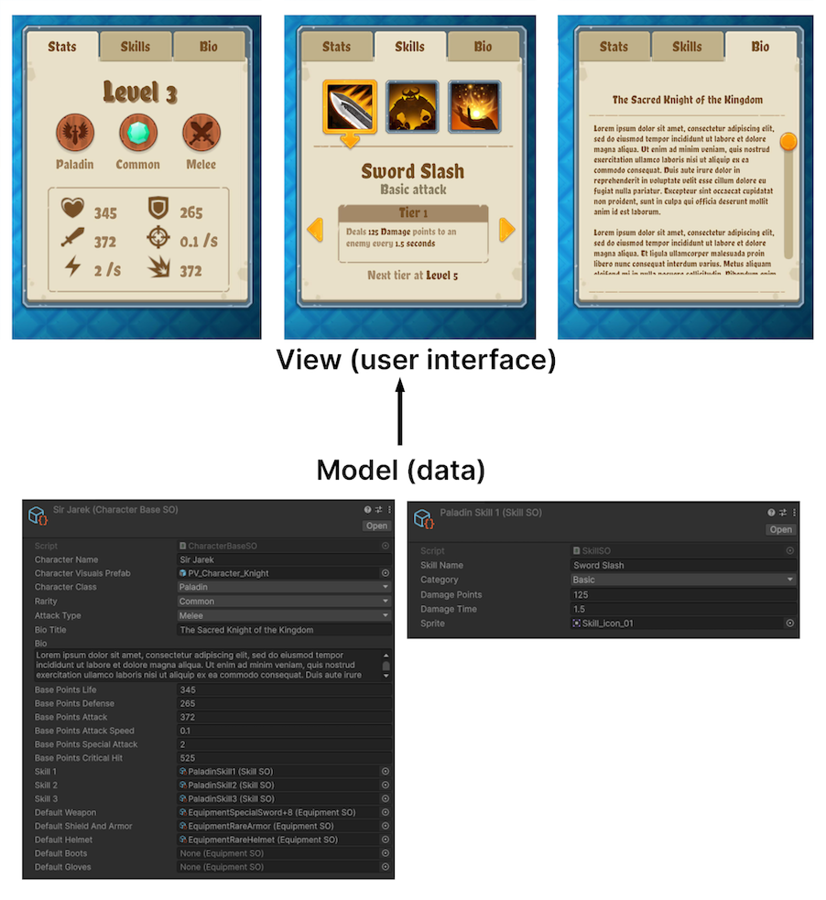

At its core, the user interface is your players’ connection to the data driving your application. It’s their primary way of seeing, touching, and engaging with your game’s internal state and logic.

Players won’t see raw stats; instead, they’ll see a health bar. Rather than reading item lists directly, they use a drag-and-drop inventory. This interplay between the UI and its data will impact how you structure your project.

UI that reflects your game data

Here’s the character stats window in UI Toolkit Sample – Dragon Crashers. This user interface shows off key attributes from an RPG-like game.

The view represents the UI itself – the part players interact with. Tabbed containers neatly organize the character’s abilities for easy navigation.

Behind the scenesA Scene contains the environments and menus of your game. Think of each unique Scene file as a unique level. In each Scene, you place your environments, obstacles, and decorations, essentially designing and building your game in pieces. More info

See in Glossary, the data lives in a model, such as a ScriptableObject storing each character’s stats.

This separation of concerns between the view and the model is a core principle in UI architecture. Decoupling the visual interface from the underlying data makes your code more flexible, reusable, and easier to manage.

However, once separated, connecting the model to the view requires some synchronization. Traditionally, this involves direct updates or event-driven systems, where observers update the UI when the data changes. While effective, these sync operations can introduce repetitive, boilerplate code.

As your project grows, these systems can become difficult to manage. Adding new elements or dependencies often requires additional update logic or event handlers. This can clutter your scriptsA piece of code that allows you to create your own Components, trigger game events, modify Component properties over time and respond to user input in any way you like. More info

See in Glossary, making them harder to read and maintain.

Enter runtime data binding

Runtime data binding in Unity 6 offers a streamlined solution to this problem. It links your application’s data directly to UI elements, ensuring that changes in one are automatically reflected in the other.

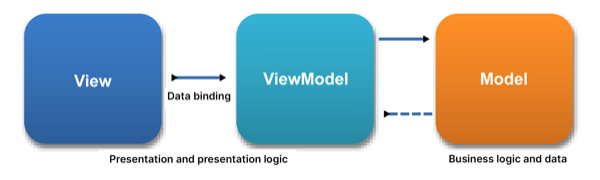

This Model-view-viewmodel (MVVM) architecture adds a layer of presentation logic between the view and model. The viewmodel acts as a mediator, exposing data from the model formatted for the view.

Learn more about MVVM along with more design patterns in the Unity e-book Level up your code with design patterns and SOLID.

For instance, a health bar can automatically display a player’s health, or a score label can update in real-time without requiring extra script logic or manual event handling. With less sync logic to manage, your project can scale more effectively.

Let’s explore examples of UI Toolkit’s runtime data binding to see how you can use it in your project.

Data binding concepts

Unity 6 introduces a runtime data binding system that provides a structured way to connect UI elements with application data. To bind a property of a visual elementA node of a visual tree that instantiates or derives from the C# VisualElement class. You can style the look, define the behaviour, and display it on screen as part of the UI. More info

See in Glossary to a data source, you will create an instance of DataBinding.

Here are a few important concepts:

Data source: This is the object that holds the data for UI bindings.

Data source path: This property or field in the data source is what the UI element connects to.

Binding mode: This controls how data flows between the source and the UI and can be either one-way or two-way.

These parts work together to create the data bindings. Let’s explore them in more detail.

Prepare a data source

A data source is the object that holds the data for UI bindings. Any C# object can serve as a data source, including ScriptableObjects, MonoBehaviours, or custom C# objects. Using structs as data sources can improve performance through lightweight memory allocations and reduced garbage collection. Data binding can be set up both through code and through the InspectorA Unity window that displays information about the currently selected GameObject, asset or project settings, allowing you to inspect and edit the values. More info

See in Glossary.

This demo project uses ScriptableObjects as data sources for their convenient ability to serialize data within the Unity Inspector.

Use the CreateProperty attribute

To expose properties for binding, UI Toolkit relies on property bags generated by the Unity Properties module. These define which properties in your data source are accessible to UI bindings.

To make properties bindable, use the CreateProperty attribute. This explicitly marks properties for the binding system. Here’s a common setup pattern:

[SerializeField, DontCreateProperty]

int m_Value;

[CreateProperty]

public int Value

{

get => m_Value;

set => m_Value = value;

}

In this example, m_Value is marked with the SerializeField attribute for serialization but excluded from binding by the DontCreateProperty attribute.

The Value property, on the other hand, is marked with CreateProperty, making it accessible to the binding system. This clear separation helps manage data flow between the model and the UI.

Runtime data bindings use property bags to traverse and manipulate a type’s data efficiently. By default, Unity generates property bags using reflection the first time a type is accessed, which adds a small runtime overhead.

To avoid this, use the CreateProperty attribute when defining properties. This generates binding code at compile time, eliminating the need for runtime reflection and reducing performance overhead.

Data sources and paths

Once your data source is ready, it can be bound to the UI. A data source path specifies the property or field within that data source that you want to connect to a UI element. For example, if your data source has a “health” property, the path would point directly to the property using it in UXML or via a binding setup in C#. Let’s look at how this looks in practice.

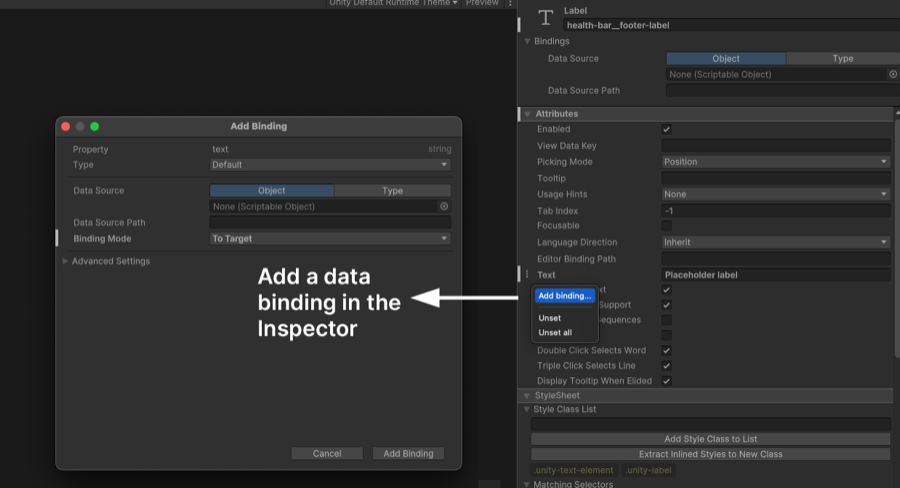

In the UI Builder: Select a Hierarchy element, go to the Inspector, and use the Add Binding option from the options (⋮) menu.

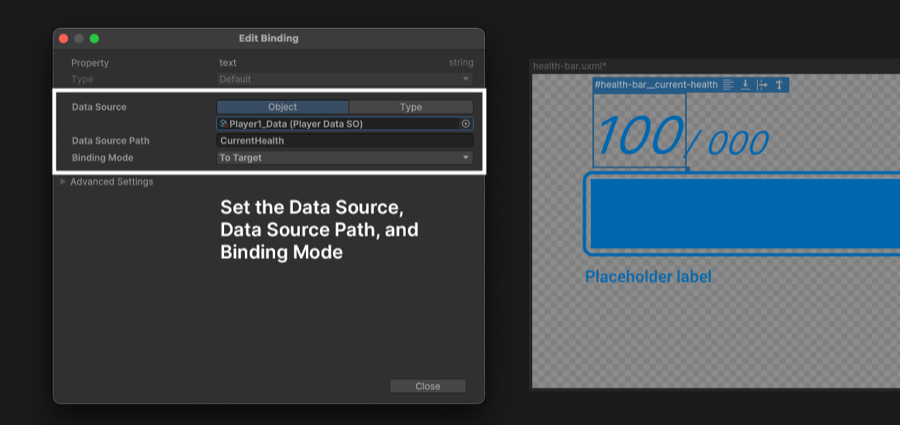

Then, assign your Data Source, like a PlayerDataSO ScriptableObject, and specify the Data Source Path, such as CurrentHealth.

In UXML: When you set up data binding in UI Builder, it generates the corresponding UXML. You can also add or edit the data source path manually in a text editor. This is the code block that creates the binding:

<Bindings>

<ui:DataBinding property="text" data-source-path="Health"/>

</Bindings>

Using C#: Instantiate or reference a data source object in your script, such as a ScriptableObject. Assign it to the dataSource property of the root element. Use the dataSourcePath to specify the exact property to bind.

Here’s a snippet that shows how to set the dataSource and dataSourcePath properties in script. We discuss this in more detail in the section below on setting up data binding in C#.

var label = new Label();

var parentData = ScriptableObject.CreateInstance<PlayerDataSO>();

playerData.Health = 100;

label.SetBinding("text", new DataBinding()

{

dataSource = playerData,

dataSourcePath = new PropertyPath(nameof(PlayerDataSO.Health)),

});

Note: It’s possible to create a conflict if you’re defining data bindings for the same UI element. To avoid confusion:

Use UI Builder/UXML bindings for static or default data configurations that don’t need runtime adjustments.

Use C# bindings for dynamic updates or cases where the data source needs to change during gameplay.

You can also set up part of the binding in UI Builder/UXML and complete the binding at runtime. See Unresolved data bindings workflow for additional context.

Inherit data sources

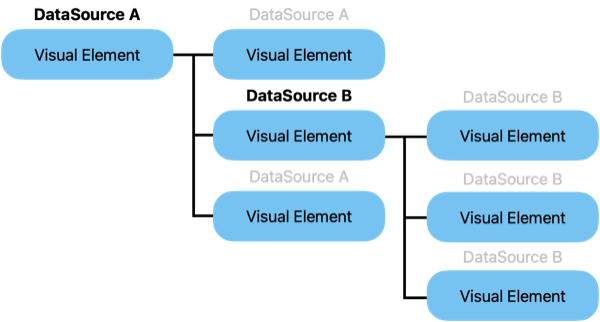

Visual elements automatically inherit the data source of their parent unless explicitly assigned a new one. For example, if the root element has a data source, all child elements use it by default. This diagram illustrates this behavior:

When a parent element has a data source, its child elements automatically inherit it. In UI Builder, the Data Source field for a child is pre-filled with the parent’s data source but can be overridden as needed.

The same inheritance logic applies when working with C#, as demonstrated in the following example:

var root = new VisualElement();

var parentData = ScriptableObject.CreateInstance<PlayerDataSO>();

parentData.Health = 100;

// Assign a data source to the root element

root.dataSource = parentData;

var child = new VisualElement();

var childData = ScriptableObject.CreateInstance<PlayerDataSO>();

childData.Health = 50;

// Override the inherited data source for the child

child.dataSource = childData;

root.Add(child);

Here, the child overrides the parent, giving it an independent data source.

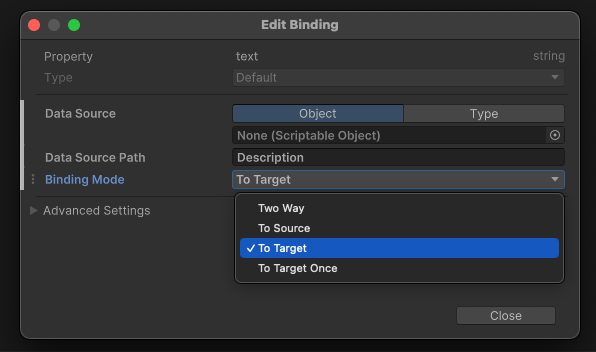

Binding modes

Binding modes control the flow of data between the data source and the UI.

These options appear in the UI Builder and C# API:

TwoWay (Default): Changes propagate both from the data source to the UI and from the UI to the data source. Use this for interactive elements like sliders or text fields where the user can change the data.

ToTarget: Data flows only from the data source to the UI. Use this for read-only UI elements.

ToSource: Data flows only from the UI to the data source. This is useful for inputs where you don’t need to display the current value initially.

ToTargetOnce: Data flows from the data source to the UI only once and doesn’t track further changes in the data source.

Example: Data binding a health bar

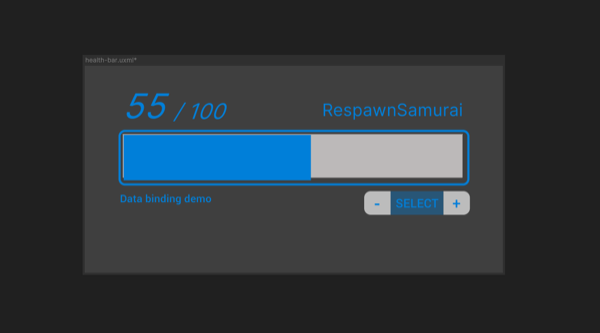

Let’s look at a practical example to see how to create some basic data bindings in UI Toolkit. Here’s an example from the demo scene – a simple health bar that dynamically updates based on a player’s health.

Demo scene

You can find the following examples in the Data Binding how-to demo included in the QuizU sample project.

To access it at runtime, navigate to Main Menu and select Demos > Data Binding, or load the DataBindingDemo scene directly after disabling the bootloader (Quiz > Don’t Load Bootstrap Scene on Play).

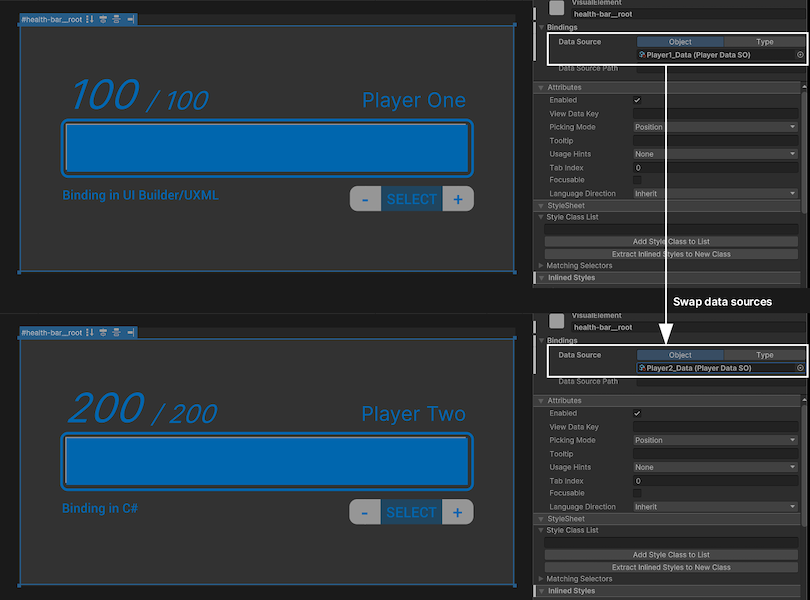

The demo scene includes two health bars, one with bindings created in UXML with UI Builder and another with bindings created in C#.

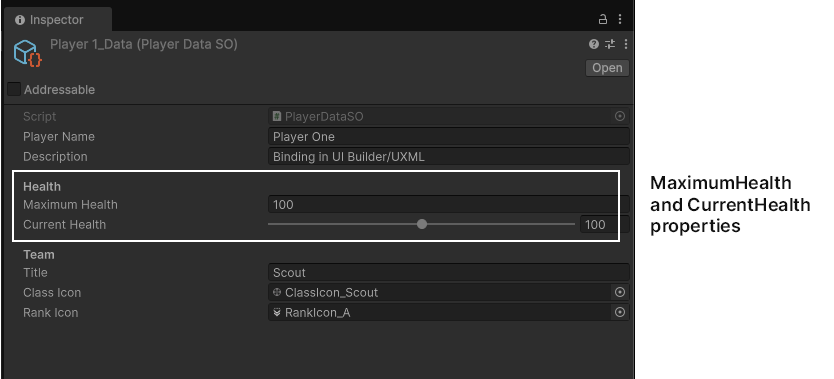

Prepare the data source

The sample project includes Player information and stats that are stored in a PlayerDataSO ScriptableObject. Relevant properties in PlayerDataSO are marked with the CreateProperty attribute, making them available for binding.

Each health bar represents only a subset of the data in PlayerDataSO, including the player name and health values. A snippet of the class shows some of its properties and related fields:

using System;

using Unity.Properties;

using UnityEngine;

using UnityEngine.UIElements;

[CreateAssetMenu(fileName = "PlayerDataSO", menuName = "Demos/Player_Data")]

public class PlayerDataSO : ScriptableObject

{

[CreateProperty] public string PlayerName => m_PlayerName;

[CreateProperty] public int CurrentHealth =>

Mathf.Clamp(m_CurrentHealth, 0, m_MaximumHealth);

[CreateProperty] public int MaximumHealth => m_MaximumHealth;

[SerializeField] string m_PlayerName;

[SerializeField] int m_MaximumHealth = 100;

[SerializeField] [Range(0, k_MaxHealthRange)]

int m_CurrentHealth = 100;

const int k_MaxHealthRange = 200;

}

The UI uses specific data paths, such as PlayerName, CurrentHealth, and MaximumHealth, to display this information visually on the screen.

Data binding in UI Builder/UXML

UI Builder offers a visual, interactive way to bind UI elements to data. It’s ideal for UI artists who prefer a design-centric workflow and developers who benefit from real-time feedback during setup. It also serves as a helpful learning tool for anyone new to data bindings.

In the demo scene, the Player One health bar’s data bindings are set up entirely in UI Builder. This involves:

Selecting the root element: Choose the root element in the hierarchy which contains the health bar. In this example, the topmost container is the demo_container-uxml element.

Assigning the data source: In the Data Binding section of the Inspector, set the data source to the ScriptableObject asset. This assigns the data source and propagates it to all child elements.

Defining data source paths: Specify the data source paths to link individual UI elements to their respective properties in the ScriptableObject (e.g.,

PlayerDataSO.PlayerName).

Once the data source is set on the root, it should appear as the default data source for the child elements. Simply fill in the correct data source path. This table illustrates the data bindings join the UI element properties with the ScriptableObject:

| UI Element | UI Element Property | Bound Property | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

health-bar__player-name |

text |

PlayerName |

Displays the player’s name |

health-bar__current-health |

text |

CurrentHealth |

Shows the current health value |

health-bar__max-health |

text |

MaximumHealth |

Displays the maximum health |

health-bar__progress |

style.width |

Progress |

Adjusts the bar width dynamically |

When the data binding is complete, the health bar updates in real-time, showing labels and a progress bar for the player’s health.

Swapping data sources is simple – just assign a new ScriptableObject asset, and the UI automatically reflects the new values while keeping the same bindings.

When you set up data bindings in UI Builder, they are added directly to the UXML file, creating a <Bindings> block for each bound element.

Here is a snippet of the resulting UXML when binding the health-bar__player-name element’s text property to the PlayerName property (some attributes are omitted for readability):

<ui:Label text="Placeholder" name="health-bar__player-name" class="health-bar__player-name">

<Bindings>

<ui:DataBinding property="text" data-source-path="PlayerName" binding-mode="ToTarget" />

</Bindings>

</ui:Label>

Experienced users can also create these bindings directly in UXML. Doing it in code can give precise control and be faster to edit when working with a lot of bindings. Hand-written UXML also offers clearer diffs for version controlA system for managing file changes. You can use Unity in conjunction with most common version control tools, including Perforce, Git, Mercurial and PlasticSCM. More info

See in Glossary, making it easier to resolve merge conflicts or track changes.

Set up data binding in C#

UI Builder is great for prototyping with static data (like pre-defined ScriptableObject assets), but runtime data often requires dynamic handling in C#. This code example shows how Player Two’s health bar works in the demo scene:

using UnityEngine;

using UnityEngine.UIElements;

using Unity.Properties;

public class HealthBar : MonoBehaviour

{

[SerializeField] PlayerDataSO m_HealthData;

public void Initialize(VisualElement root)

{

var m_PlayerName = root.Q<Label>("health-bar__player-name");

root.dataSource = m_HealthData;

m_PlayerName.SetBinding("text", new DataBinding()

{

dataSourcePath = new PropertyPath(nameof(PlayerDataSO.PlayerName)),

bindingMode = BindingMode.ToTarget

});

}

}

The HealthBar script handles this in its Initialize method, which is called from the main controller script in OnEnable.

First, we query for the

health-bar__player-nameelement. Then, we assign the ScriptableObject data as a source.The

SetBindingmethod then binds thetextproperty to a new DataBinding instance and sets thedataSourcePathandbindingModeparameters.

All four bindings in the above table are set up similarly. Use the ScriptableObject slider or custom Editor property drawerA Unity feature that allows you to customize the look of certain controls in the Inspector window by using attributes on your scripts, or by controlling how a specific Serializable class should look More info

See in Glossary to adjust the CurrentHealth. The demo includes play test controls (+, -, Select) to increment, decrement, or select the ScriptableObject. The health bar updates dynamically as the changes occur.

Unresolved data bindings workflow

Unity 6 also supports a hybrid data binding workflow that blends UI Builder’s visual setup with the flexibility of scripting.

Instead of hard-coding data sources in UXML, you can specify a Data Source Type and leave the actual data source unresolved. UI Builder marks these incomplete bindings with a hollow icon. This means that the paths and types are set but the data source is not yet assigned.

At runtime, you can assign the data source with just one line of code. For example:

myElement.dataSource = myNewDataSource;

Here, assigning the myNewDataSource to myElement resolves the placeholder bindings defined in UXML, allowing the UI to update automatically. This eliminates repetitive SetBinding calls and keeps the UXML flexible.

The Dragon Crashers sample, for example, predefines data paths in UXML while setting the actual data sources at runtime.

Clicking the next and last buttons in the UI sets the currently selected character as the data source. Changing the data source requires no modification to the UXML.

The unresolved bindings show the correct character stats once the new data source is set.

Note: If the UXML file sets a specific data source (e.g., data-source="PlayerDataSO.asset"), the binding becomes fixed and cannot be altered at runtime. To enable runtime changes, leave the data-source attribute empty or use a data-source-type instead.

See Binding a list to a ListView for an example of this hybrid data binding workflow.

Type converters

Type converters in Unity 6 allow you to transform raw data into more user-friendly formats for display in your UI. They act as intermediaries between your data source and the UI, transforming the data into a more intuitive format for the user.

For example, type converters can convert radians into degrees or raw health values into colors for a health bar. This allows the UI to present information in a format that’s clear and easy to understand. Type converters do this without requiring a lot of manual transformation logic.

Unity 6 supports two categories of type of converters:

Global converters: Apply these to any bindings that need a specific type conversion. For example, global converters can turn any float health percentage into a color value or convert

Colorobjects intoStyleColortypes, ensuring consistent behavior across your UI.Per-binding converters: Apply these to specific data bindings for more granular control.

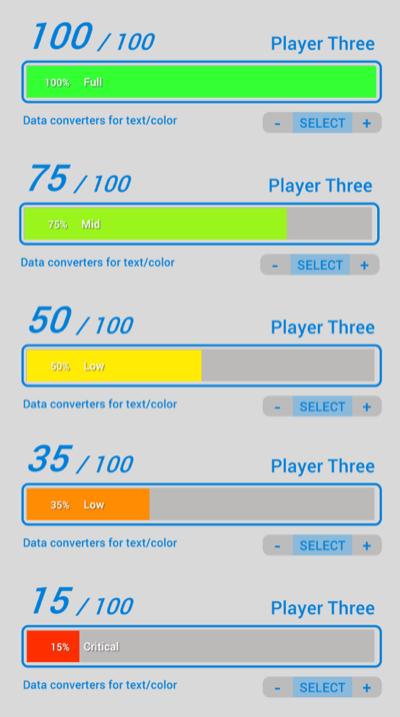

Example: Convert a value to a color

A health bar that changes color based on the player’s health illustrates the use of a data binding with a type converter. By mapping the player’s current health to a color gradient (e.g. green for high health, yellow for low health, and red for critical health), players can quickly gauge their status during gameplay.

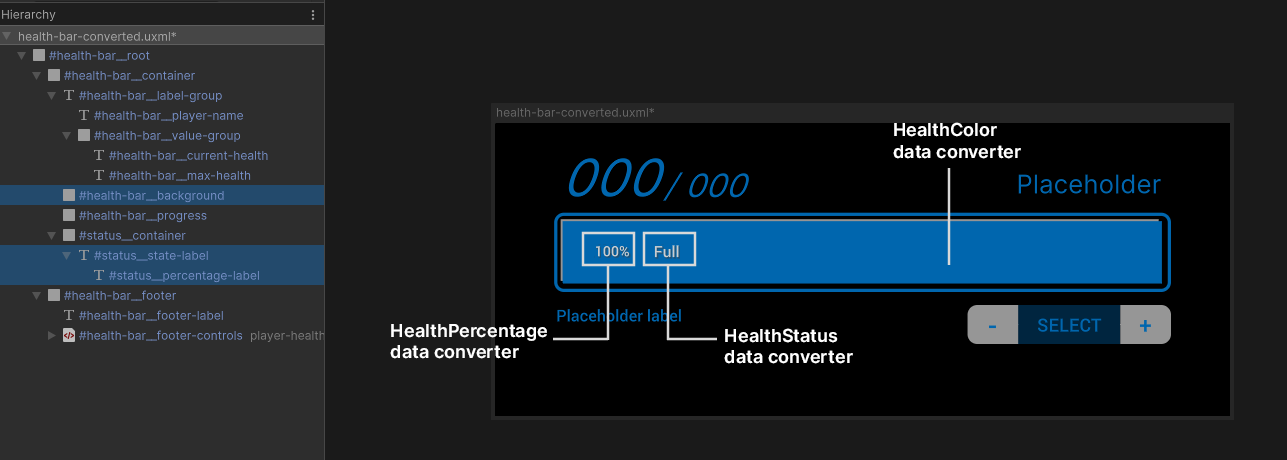

You can see this in action in the DataBindingDemo scene within the QuizU project.

HealthDataConverter setup

In the DataBindingDemo scene, the HealthBarWithConverter class uses some functionality from a static HealthDataConverter to register a few DataConverters:

The health percentage drives a color gradient for a health bar, transitioning from green (full health) to red (critical health).

A label can represent the numerical value as a percentage string (e.g., “75%”).

Another label can map the same health percentage to a status label like “Full,” “Mid,” or “Critical.”

Here’s a snippet of the HealthDataConverter class:

public static class HealthDataConverter

{

static readonly Color s_FullColor = new Color(0.2f, 1f, 0.2f);

static readonly Color s_MidColor = Color.yellow;

static readonly Color s_LowColor = new Color(1f, 0.3f, 0f);

static readonly Color s_CriticalColor = Color.red;

public static void Register()

{

RegisterHealthColorConverter();

// ...

}

static void RegisterHealthColorConverter()

{

var colorConverter = new ConverterGroup("HealthColor");

colorConverter.AddConverter((ref float healthPercentage) =>

{

if (healthPercentage > 0.5f)

{

return new StyleColor(Color.Lerp(s_MidColor, s_FullColor,

(healthPercentage - 0.5f) * 2f));

}

else if (healthPercentage > 0.25f)

{

return new StyleColor(Color.Lerp(s_LowColor, s_MidColor,

(healthPercentage - 0.25f) * 4f));

}

else

{

return new StyleColor(Color.Lerp(s_CriticalColor, s_LowColor,

healthPercentage * 4f));

}

});

ConverterGroups.RegisterConverterGroup(colorConverter);

}

// ...

}

The above logic creates a HealthColor ConverterGroup, which transforms a float health percentage (from 0 to 1) into a matching StyleColor value between red (low health) and green (full health).

The HealthDataConverter class also includes converters for the two labels. These can represent the HealthPercentage property of the PlayerDataSO as formatted string values. Although you can bundle multiple converters into a single ConverterGroup, this demo separates them into distinct ConverterGroups for readability.

The HealthBarWithConverter

Note that the HealthDataConverter class contains the actual functionality. The HealthBarWithConverter is simply:

public class HealthBarWithConverter : HealthBar

{

#if UNITY_EDITOR

[UnityEditor.InitializeOnLoadMethod]

#else

[RuntimeInitializeOnLoadMethod(RuntimeInitializeLoadType.SubsystemRegistration)]

#endif

public static void RegisterConverters()

{

HealthDataConverter.Register();

}

}

Note the following:

UnityEditor.InitializeOnLoadMethodensures the ConverterGroup is registered and available for the UI Builder, allowing you to see and apply it in the Editor.RuntimeInitializeOnLoadMethodensures the ConverterGroup is available during runtime when the game is running.

The #if UNITY_EDITOR preprocessor directive ensures the appropriate method runs, depending on whether the code executes in the Editor or during gameplay.

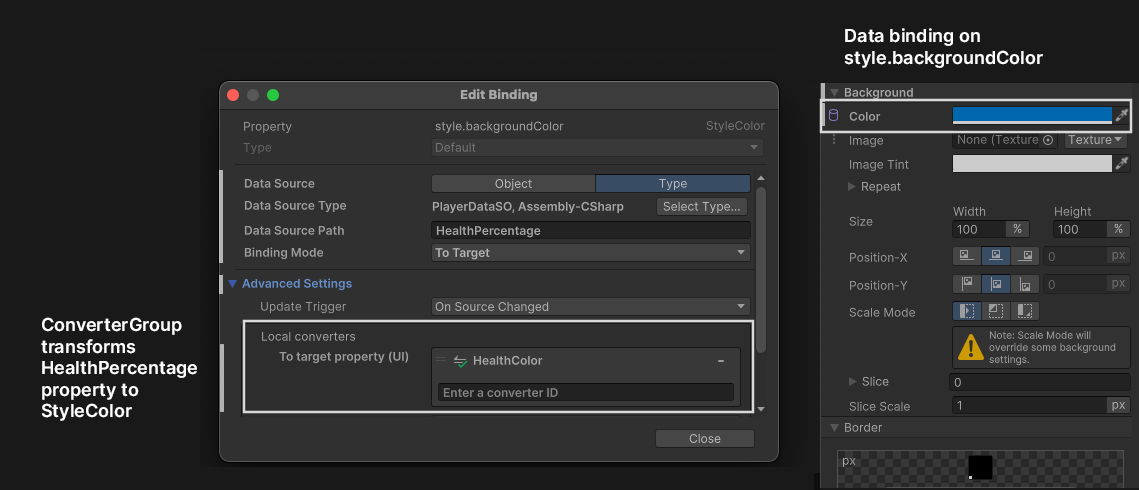

DataConverter application in UI Builder

Once registered, this DataConverter can be applied to any binding that needs this conversion. To use it directly in the UI Builder:

Open your UXML file and select the progress bar element. In the QuizU project, you can open the RuntimeDataBinding.uxml file to see how it’s set up.

Set the Data Source to your

PlayerDataSOScriptableObject.Bind the progress bar’s

backgroundColorstyle property to the HealthPercentage data path.-

Use the

HealthColorConverterGroup to transform the health percentage value into a color background for the progress bar.

Set up the data binding for the health bar. Dragging the

CurrentHealthvalue of thePlayerDataSOScriptableObject now updates the health bar color. The gradient smoothly lerps from green (full health) to yellow (medium), orange (low), and red (critical).

This global DataConverter is now available anywhere in your application where you need to convert a float value to this color gradient.

Best practices

When working with type converters, keep these tips in mind:

Minimize allocations: Keep conversion delegates lightweight, especially for frequent operations, to avoid unnecessary performance overhead.

Keep it simple: Write simple, focused converters for quick transformations. Avoid embedding complex or resource-intensive logic.

Integrate conversion into the data source: Handle basic conversions in the data source itself (e.g., pre-format health percentages in a ScriptableObject property). Reserve DataConverters for conversions specific to UI bindings.

Example: Bind a list to a ListView

Depending on your game UI, your application may need to display dynamic lists of data, like a character inventory listing items, a quest log tracking objectives, a leaderboard ranking players, etc.

A ListView offers a clean, scrollable interface that makes it easy to manage and present this information. Unity 6 streamlines this process with runtime data binding, eliminating the need for manual updates or custom scripts to refresh the UI when data changes.

In earlier versions of Unity, setting up a ListView required writing custom code to populate the list and handle updates as data changed. With Unity 6, a ListView can bind directly to a data source, automatically tracking and reflecting changes in the UI.

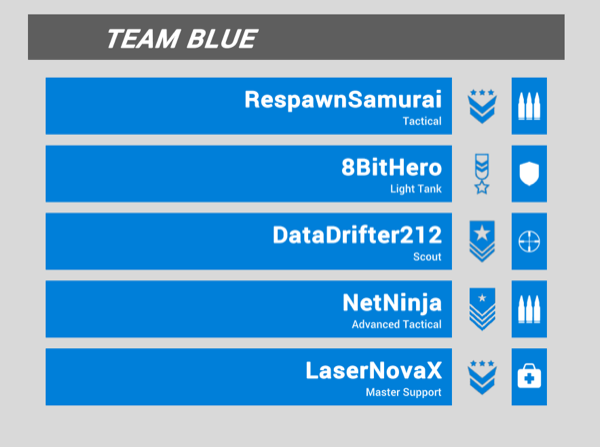

The demo scene includes a simple ListView that binds to a list of PlayerDataSO ScriptableObjects. This lets us create an interface similar to one found in a multiplayer game lobby or high-score leaderboard.

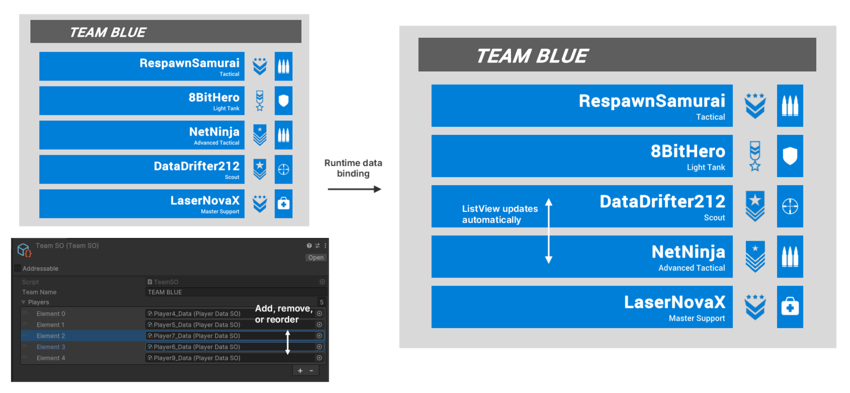

With runtime data binding, you can link a ListView directly to a data source, such as a ScriptableObject. The ListView automatically tracks changes to the data, streamlining setup and maintenance.

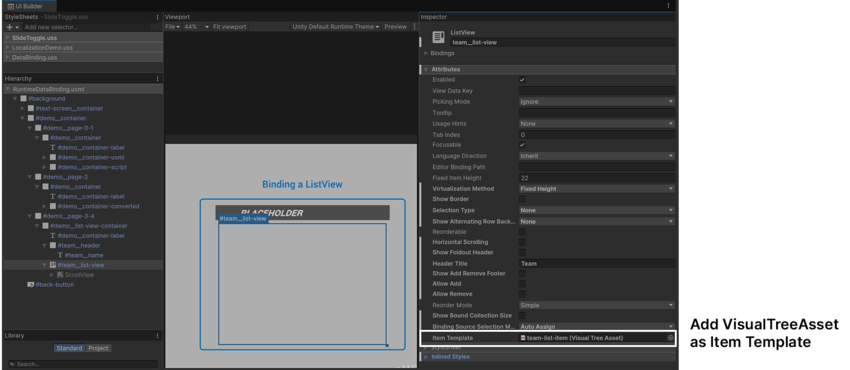

Data binding a ListView to a list involves setting up some unresolved bindings and then completing the data binding at runtime.

Set up the list and templates

To set up the list and templates, use the following three-step workflow:

Define a data source: Your ListView needs a list of data. In this demo, a TeamSO ScriptableObject holds a list of PlayerDataSO objects. Each item in that list corresponds to a row in the ListView.

-

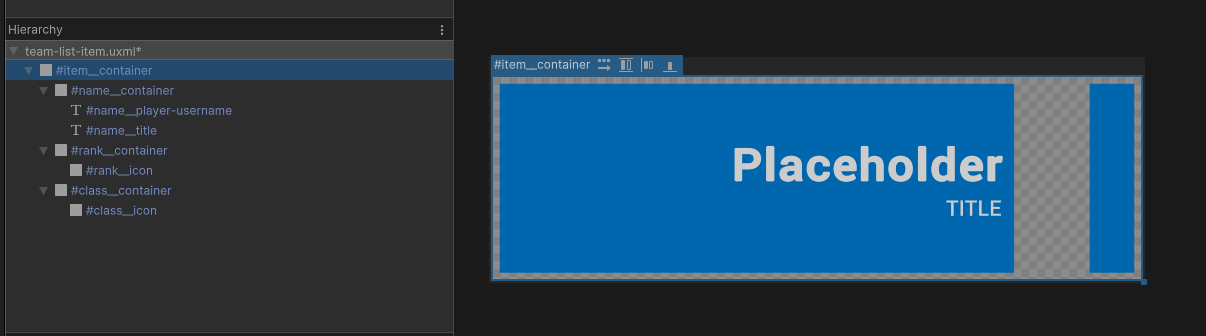

Create a UXML item template: In the UI Builder, design a UXML template (a VisualTreeAsset) that defines what a single list item looks like. For example, the

team-list-itemtemplate in the demo includes a player’s name and some Texture2D properties. Instead of directly referencing a data source, set a Data Source Type and Data Source Path in UI Builder. This leaves the binding unresolved, ready to be completed later at runtime.

Design a visual tree asset in UI Builder. Add the ListView to the main user interface: In another UXML file, add a ListView element that will display the entire list of players. Assign your item template as the ListView’s Item Template. At this point, the ListView knows how each row should look, but it doesn’t know which specific data source to use yet.

The demo scene’s ListView uses only a few basic settings (shown above). For more advanced features, consult the official ListView documentation.

Complete the binding at runtime

At runtime, a simple TeamList script finalizes the binding by providing the actual data source. These lines complete the previously unresolved bindings:

// Set the data source

m_ListView.dataSource = m_TeamData;

// Bind the "itemsSource" to the Players list

m_ListView.SetBinding("itemsSource", new DataBinding

{

dataSourcePath = new PropertyPath("Players")

});

Here, m_TeamData (an instance of TeamSO) is assigned to the ListView. Calling SetBinding once associates the Players property with the itemsSource. This allows the ListView to populate the rows of the UI.

Because these bindings remain unresolved in the UXML until runtime, you don’t need to individually connect each list element. UI Toolkit resolves these bindings on its own and fills in the data for every list item.

Any changes to the list in the data source (e.g., adding, removing, or rearranging players) immediately appear in the UI without requiring further scripting.

Remember that this hybrid approach to data binding can reduce a lot of repetitive boilerplate code. By setting up placeholder data paths in UXML, you can postpone assigning the actual data source until runtime.

If you change the data model, there’s no need to rewrite your entire binding logic. A single update at startup can rewire the UI to the new source.

For a comprehensive look at binding a ListView to a list, refer to this documentation page.

Optimize data binding

Efficient binding can help you maintain a performant UI. Redundant or excessive bindings can overload the system, leading to unnecessary updates and reduced performance. This is especially important if your interface is complex or resource-intensive.

By default, the runtime binding system updates UI elements every frame. This is responsive for a small application but can become a performance bottleneck with more bindings.

This section covers methods to improve data binding efficiency for larger projects.

Manage value types

If your data source uses value types (e.g., int, float, struct), watch out for boxing costs. Because the dataSource property operates as an object, frequent conversions from value types can add overhead.

To reduce this, minimize unnecessary bindings or redundant updates when working with value-type properties.

Minimize overhead

Start by identifying bindings that update the same elements multiple times or track data that rarely changes. Consolidate or remove these bindings to reduce unnecessary work. Use flat, simple data structures instead of complex hierarchies when possible. This can avoid performance bottlenecks caused by frequent data lookups.

Consider precomputing or caching values that require heavy calculations. Binding to these precomputed values reduces the computational load on the binding system and avoids repeated recalculations.

Make sure your bindings are only on elements that need frequent updates. For elements that don’t require constant synchronization, remove unnecessary bindings and instead assign values directly or update them only when triggered by events.

Use update triggers

Bindings refresh based on update triggers, which determine how often the UI synchronizes with the data source. This allows you to balance performance with responsiveness. These options determines how often the bindings update:

Every frame: This updates continuously. Use this for elements that require constant updates, like the example health bars.

On change detection: This updates when the data source changes, or every frame if detection isn’t possible. For instance, use this for stats panels or inventory lists that depend on observable data.

When marked as dirty: In scenarios where updates are infrequent, explicitly marking bindings as dirty with

MarkDirtyavoids unnecessary refresh cycles. This update triggers works for elements like settings menus that change only in specific contexts.

By matching update triggers to the needs of each UI element, you can balance responsiveness with efficiency.

Versioning and change tracking

To reduce unnecessary updates, you can integrate versioning and change tracking into your data sources.

Two interfaces can help make your data binding more efficient:

IDataSourceViewHashProvider: This tracks overall changes using a version hash, triggering updates only when the data source changes. This is useful for static or semi-static data, where updates are infrequent.

INotifyBindablePropertyChanged: This tracks changes at the property level, ensuring that affected bindings are refreshed. This offers granular control.

Add these interfaces to the data source. They can be used independently or together for greater control over updates. Refer to this documentation page for usage and best practices.

💡 Tip: More UI Toolkit optimization tips

In this Unite 2024 talk on UI Toolkit optimizations, you’ll learn about topics like the chained draw-calls implementation and the implications of buffer sizes, dynamic atlasing best practices, and dealing with limitations like custom shadersA program that runs on the GPU. More info

See in Glossary and 3D UI.